Friday, February 26, 1988

New York Times / Jack Manning

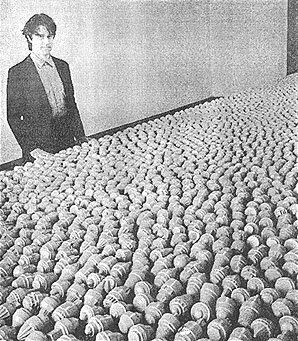

Allan McCollum with a portion of "Individual Works," consisting of over 10,000 different sculptures laid out on a table of black velvet. It is on view at the John Weber Gallery.

Art People | Douglas C. McGill

Over 10,000 sculptures that, like people, look the same in a group but different individually

mong those artists who work the common ground between fine art, installations and pure theater, Allan McCollum is among the most provocative. He is best known for paintings that are not really paintings — they are plaster casts of frames that frame only an empty black or colored field — and for putting dozens, hundreds and even thousands of them up on a gallery wall all at once.

He has struck again, now, with a performance of repetition at two galleries in town - the John Weber Gallery, at 142 Greene Street, and the Anina Nosei Gallery, at 100 Prince Street. The Anina Nosei presents works of a sort we've seen before, namely surrogate paintings, but something new has cropped up at the John Weber.

Here are over 10,000 sculptures, each roughly the size and shape of a hand grenade, all laid out on a table of black velvet, 66 feet long and 7 feet wide. From a few feet, the sculptures, called "Individual Works," look identical; upon closer inspection, each is revealed to be different, each being made from a different combination of Hydrocal casts of household objects like furniture finials, spray can caps, medicine jar lids and plastic Easter eggs.

"Why are our feelings about abundance never expressed in the way we make art?" Mr. McCollum asked the other day during an interview at the Weber. "It's as if art wants to deny abundance, as if people want to see a work of art as a rare, irreplaceable thing. These are irreplaceable, but they are not rare."

Mr. McCollum, a native of Los Angeles, suggested that a key to his work lies in his background, especially in the fact that both parents worked in factories, mostly for the aerospace industry.

"I came from a family of factory workers, and I have an emotional involvement in the idea of repeated actions and tasks," he said. "I don't find them to be as much a waste of time as a person might who didn't grow up in such a family."

"I'm very interested in how being distinguished as a working-class person affects your life," he added. "I think I attempt to resolve my interest in fine arts with my background all the time."

As for exactly where the emotional interest lies in repetition, the artist suggested that the pieces in his "Individual Works" looked indistinguishable as a crowd but unique as individuals — something like people.

"As soon as you talk about the group and the individual, you're talking about the human soul, or something like that," Mr. McCollum said. "There is always some emotional investment in quantity, which you get whenever you look at masses of anything, whether it's nails or bricks or whatever. Quantity is something you have a feeling about."